First is Prof. Seppe Deckers, professor emeritus of KU Leuven, President of the Society:

Seppe Deckers has his heart in the field with a special interest in soil –landscape relationships. After his PhD at KU Leuven University he was fielded for 10 years in Tanzania and in Ethiopia under the Land and Water Division of FAO. In 1990 he joined the Division of Soil and Water Research at KU Leuven where he has been teaching Soil Geography, Land evaluation, Soil Mapping and Soils of the Tropics. Seppe has been actively contributing to the development of the World Reference Base for Soil Resources since its inception in 1991.

SSSB: If you have to choose a favorite soil, what would it be?

Seppe Deckers: a Luvisol

SSSB: What are the main properties of this soil type?

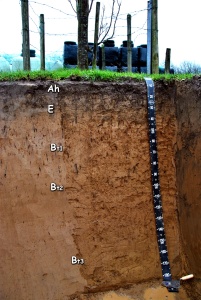

Seppe Deckers: Luvisols are soils with a typical accumulation of high-activity clays in the subsoil. With their high base saturation they can be considered as reasonably fertile soils. The Luvisols are dominant in the agricultural land of the loess belt of central Belgium.

SSSB: Why do you find this soil type particularly interesting?

Seppe Deckers: When I was about 10 years old, I remember digging a pit in our garden and getting almost stuck in the subsoil. My father came to the rescue and explained me why it felt so sticky heavy and called it ‘clay’. Clay for making pottery I thought, so I molded it into small candle holder. However, while baking it my mother’s kitchen stove it broke up into 1000 pieces – so I concluded that the clay was strong enough to pull itself apart when drying out – I got inspired and wanted to know more about it! From scientific point I like Luvisols because most of them have been shaped by some 1000 years of agriculture, they are soils that tell a story about the history of agriculture in central Belgium. On that ground we could in fact consider them as a special type of man-made Anthrosol.

SSSB: Do the properties of this soil type have consequences for it’s management, e.g. in terms of land use, soil quality, conservation, … ?

Seppe Deckers: Very much so – first of all, the high clay content in the subsoil represents an important reserve of food and water for the plants or crops growing on the land. Below one square meter of a Luvisol between 15 – 20 buckets of water is readily available – so plants can bridge the dry spells during our summer months. Under a well- nourished pasture Luvisols may provide home to 10 million earth worms. Hence with some 4– 5 tons of worms there may be even more animal biomass in the soil than in the animals grazing on top of it.

The major threat for Luvisols is related to the very composition of its parent material having a very high silt content: soil erosion. Soil losses by water, and tillage erosion have been enormous over the last 50 years, so much that in many of our soilscapes we only can find strongly truncated Luvisols, or a residue that is a far cry from what could be called a Luvisol.

SSSB: Can you tell us your most memorable story concerning this soil type?

Seppe Deckers: I’d like to recall that late Prof. Rudi Dudal established the concept of the Luvisols in Belgium when he was mapping central Belgium. He refuted the then generally accepted theory of Luvisols being the result of two superimposed geological layers (the so called lithological discontinuity theory!). He humbly acknowledged Guy Smith showing him the coatings in the field and under the microscope. While doing his PhD research at Leuven, he was the first one to explore the famous paleosol of Rocourt. Dudal’s proposal to interpret Rocourt as an older-generation soil in equilibrium with an interglacial climate some 100.000 year ago was confirmed later on by numerous renowned scientists. However, the age of the Luvisols in our agricultural landscape remained an issue of hot debate till very recently. Did Luvisols evolve during the Atlanticum period under a relatively warm and balmy climate as suggested by Dudal and Gullettops or were they originating from a much earlier Late Glacial time (Langohr and Van Vliet)? A simple topographic transect in Bertembos shows that the answer depends on the geomorphological context: the two generations of Luvisols occur next to each other, the Atlantic one on the steep slopes and the Dryas ones in plateau and valley-bottom situations. However, are the latter ones Luvisols in WRB 2014? The imprint of the glacial structures, the albeluvic tongues, remain so well conserved and strongly expressed that they deserve another of my favorites: Retisols.